Tucked away in the northwest corner of Spain, bordered by mountains to the south and the east, and exposed to the ravages of the Atlantic on its coasts, lies the land of Galicia. This is the part of the Iberian peninsula where the Celts came to call home many moons ago. The lush, green, rainswept landscapes abound in vegetation, and look far more like other Celtic countries to the north than they do to most of mainland Spain. Galicia is a land that seems lost in the fog of time. Its countryside is dotted with tiny lifeless stone villages, where many buildings are crumbling from lack of use or attention. Horreos, those curious grain stores shaped like mini churches on stilts, appear regularly along the roads as spectral reminders of the area’s disappearing farming traditions. Yet in spite of its fading way of life, this mystical land remains a major draw for people from every corner of the globe, for all camino routes end in Galicia. This region is the home of Santiago de Compostela, the tomb of the apostle St. James, and the final destination for tenacious pilgrims after weeks or months on the road.

Galicia’s rugged terrain can be demanding on the body, but its unpredictable climate may be its biggest test of character. This is a land of rain. Not misty mornings or showery afternoons, but apocalyptic deluges that batter and pound the grounds, causing rivers and streams to swell and flood, and inspire fear, terror and desperation into the hearts of even the most hardy of pilgrims. If you come to Galicia you know you must prepare for a meteorological beating of biblical proportions. It can make or break your equipment, character and will to live. Whatever your religious persuasions, you have to hope and pray that there is a higher power above looking out for you as you cross this demanding country. It is said there are no atheists in the foxhole, and it would be a foolish pilgrim who comes to Galicia and doesn’t carry some supernatural beliefs as insurance. Saint James can be a very valuable transcendental ally as you follow the paths to his resting place.

I’d been walking for 29 days by the time I reached the border of Galicia, and on a normal camino I’d be near Santiago by now. Not so this time. I had another week to go before I reached that point, but as ever I had to keep putting one foot in front of the other. My equipment was started to wear down; my walking poles, which had been with me on each on my previous caminos, were coming to the end of their own road, as was my backpack. The soles of my boots were springing leaks as well. I would retire all these items with honour when I finished, but they still had a lot of work to do before they could be put out to stud.

The walk in Galicia began with a descent of a mountain, along a rustic path that wound its way through leafy forests, and across luscious meadows full of brown cows with bells around their necks. Small streams twisted and flowed through the woods, and a light gentle mist swirled around the atmosphere. Not another living soul was to be seen in this splendid stretch of untrammelled nature. Traversing isolated craggy moors, verdant scrublands and fertile farms, the path continued through a scattering of empty hamlets before reaching the small town of A Guidina, where I was going to spend the night. While Galicia’s old stone villages had a picture postcard whimsey about them, its towns were rarely the model of attractiveness. In fact, many of them looked like they’d been drafted by an uninspired town planner using an algorithm designed by an unimaginative bureaucrat. If either of them had even the good sense to get drunk before going to work they might have turned out places with more panache. Seeing these towns through the dreariness of autumn weather, as I usually had, didn’t help their cause either. A Guidina wasn’t likely to be on a list of tourist hotspots in a country that boasts the Alhambra, the Sagrada Familia and the Costa del Sol, but it did have a shop where the owner gave out free figs to his customers, so that made it just fine in my book.

Galicia has a good network of municipally run albergues. Many are modern, they’re usually clean and well maintained, and even with the whopping €2 increase that was introduced in 2019 they’re still good value for money at €8 per night. Around a dozen determined pilgrims had made to A Guidina, with a mixture of nationalities from Europe, the Americas and Asia staying in the town’s spacious refuge. Virtually everyone had walked around 800 KM to reach this point, and we would see this journey out come hell or high water. And high water seemed to be on the cards for the following day. The weather had held out on us until this point, but all that was about to change. The next stage saw a long hike of 34 KM to a place called Laza, which involved a few hefty climbs and then a descent of about 700 metres. It was supposed to be one of the most beautiful stages, but the forecast was for rain, and Galician rain at that. There was a town called Campobecerros after 20 KM, which was an alternative stopping point if people found the weather too troublesome, but even for the stubborn people who were prepared to take a meteorological beating there could be a day of challenges ahead.

After surviving a day of apocalyptic rain on the way to Finisterre in 2013 I had always faced into storms with a curious mixture of fear and excitement. There are few experiences on the camino that are more debilitating than getting a biblical soaking, but oddly enough there are also few that are more exhilarating. As the clocks had gone back the previous Sunday we now had an extra hour of daylight in the morning, but when a thick heavy fog descended on the countryside it made the temporal adjustment academic. I set off at 8, and faced into a persistent headwind spitting light rain into my face. I met two Italian friends, Flora and Enzo, further ahead. We chatted for a while, and I helped them adjust their ponchos which were being blown ragged by the oncoming gusts. I carried on by myself after a while, and followed the arrows up a mountain. There were supposed to be heavenly views of the Galician countryside from here, but I couldn’t tell whether I was looking down into the Valley of the Kings or the Valley of the Damned as a fog as strong as a Russian bodybuilder on steroids was sitting on top of me. Getting lost had always my greatest fear on the camino, and these conditions were the perfect opportunity to go so far off course I could literally end up in another country. After all, Portugal was only a few kilometres to the south.

I floundered through the heavy fog as I trekked my way uphill and battled along the craggy paths, not knowing what lay in front of me or to my sides. Had I closed my eyes and walked with just hope in my heart I wouldn’t have found the journey any less arduous. Everyone once in a while I saw a yellow arrow, which to a pilgrim in such circumstances was like finding gold to an 1840s prospector. The air cleared as I descended that mountain, and I saw the new tracks for the high speed train tear their way through the landscape beneath. I made my way through the higgledy piggledy town of Campobecerros, and decided the weather was bearable enough for me to plough on for a few more hours. I could get a sense of the beauty of the surrounding countryside, but it was becoming increasingly obscured by thickening fog and heavier downpours to the point where it became invisible. The long descent began shortly afterwards and it was more forgiving and accommodating than the rain, whose intensity fluctuated from annoying to menacing. I followed a winding mountain road through a rich forest displaying all its autumnal tones. Occasionally some gaps in the mist allowed brief, tantalising panoramas of the hills and woodlands in the distance, but in the main visibility was as limited as employment opportunities for philosophy graduates. On a clear and sunny day this would have been a heavenly walk. Today it was just a test of character. The rain and fog made the road seem longer, my bag heavier, and my leaky boots were taking in enough water to sink the Titanic. My rain gear worked about as efficiently as an affordable Italian car, but in the end of the day it was arduous experiences like this that had made me want to walk the camino in the first place.

I trundled on to the beautifully ugly town of Laza to recuperate, where a change of clothes and a warm shower were enough to wash away the challenges of a long walk in the rain. Following a hearty dinner and a good night’s sleep I was ready to do it all again the next day, which was Halloween. In all my years I’d had the good fortune to spend Halloween in places as exciting as Rome, San Francisco, Barcelona, Istanbul and Kathmandu. The place I was heading for this halloween was a little village called Xunqueria de Ambia, about 33 KM away. Not exactly an iconic location, but I’m sure it would have some charms of it own. The walk began with a mini Mount Everest. The climb was steep, but en route I met Herman, my 79 year old Austrian friend doing his 18th camino. He bounded up the path like a sure footed mountain goat, leaving everyone else with no excuses. Growing older is a fear I have buried in the fog, hoping that the air never clears and I don’t have to confront the ageing process full on. I’ve looked after my health and fitness levels sufficiently to have offset the onset of middle age, but when I saw the speed and agility of Herman, I felt I could continue to live in denial of my advancing years for another couple of decades. Cliched and all as it is, age really is just a number, especially when you meet someone like Herman. He may be exceptional, but he was also inspirational.

Once the mountain plateaued the camino progressed further into the heartland of Galicia, whose landscape was now exhibiting its richest flush of seasonal colours. These could be experienced in all their glory especially since the previous day’s rain had not reappeared. The countryside was a pleasant mixture of woodlands, little stone villages connected together like a string of beads, and flat, expansive cornfields reminiscent of the Meseta. After stopping to have lunch deep in a dark deciduous forest, I passed by an apiary on the crest of a hill. The buzzing of the busy bees played out in full stereo, but then a few swarmed a little too close for comfort and one flew inside my shirt. I removed my hat to brush the little bastard away and then another one bit me on the back of the head. I started to have visions of contracting rabies or some other life threatening condition. I thought that my greatest fear of my camino being cut short would eventually come to pass. I’d survived wayward dogs, hunters, wild boar, the punishing heat of the Extremaduran sun, the biting cold of the Meseta, but in the end it would be a humble bee that would fell this pilgrim, and just five days from Santiago at that. My head would swell, my blood stream would be poisoned, my heart would explode, and I would die right there on the spot. Or I might just have a small irritating lump for a couple of days. Perhaps I would get to Santiago after all.

The impressive 12th century Monasterio de Santa Maria la Real is Xunqueria’s centre piece, and, unlike most of Galicia’s churches, it was actually open when I wanted to go in. The adjoining cloisters offered a quiet space for contemplation. I’ve always liked cloisters, and seek them out whenever I get a chance. There’s something deeply meditative and calming about walking slowly and reflectively around their four stone corridors. I spent some time in there in the early hours of the evening, thinking about where I was, how far I’d come, and how close I was to my destination. I knew that the pilgrimage had been physically demanding, but I recognised that I was also very fortunate to be able to do it. Having six weeks of free time to traverse a country on foot and live a life of intense frugality is indeed a luxury in the modern world. Even getting stung by a bee in a mountain apiary is essentially a bit of an extravagance. That wouldn’t have happened if I’d spent the month of October in an office like a normal person.

The following day was the first of November, All Souls Day, another holiday in Spain and thus a guarantee that whatever shops I found would be closed. I was now entering the business phase of the camino, which was evident because of the frequency of road signs indicating the distance to Santiago. I was heading to Oursense, a large city famous for its thermal baths, which would mark the beginning of the last 100 KM. I set off from the albergue in Xunqueria and hastily exited the village by taking a turn that led me along a wooded path by a riverbank. There were horizontal yellow and white stripes on some of the trees, indicating that this was a path of some description, but I couldn’t find any regular yellow camino arrows. I had travelled a sufficient distance before I realised I’d probably taken a wrong turn. I could double back, but it was difficult to trace the path I’d travelled through this thick forest, and because of the persistent shortage of finding bread in Spain I hadn’t been able to leave a trail of breadcrumbs to mark my passage either. I decided to forge on and hope that I would find the way.

I had never been very lost on any camino, not literally anyway, but going far off path had been one of my biggest sources of anxiety. I had missed an arrow in a forest in central Portugal once, and ended up adding several kilometres onto my journey on a hot and thirsty day. But I got to where I was going that evening, and I learned that everyone else in the albergue had also taken then wrong route. Today my situation was different. I knew I was lost and I wanted to carry on into the unknown to prove to myself that the worst was not going to happen. All my life I’d been a worrier, and had that been an Olympic sport I’d have been a contender for gold. But having spent months of my life on the camino, living far outside my physical and mental comfort zones, I’d learned valuable lessons in resilience and I wasn’t too fazed by anything from angry bees to deer hunters anymore.

I thought back to my very first camino, and how terrified I was when I reached the bus terminal in Pamplona. It was from there that I would get transport to Roncesvalles, where I was due to begin my walk. I had a five hour delay from the time I arrived until the bus departed, and I was afraid to leave the bus station for fear of getting lost – and then missing the bus, and being left stranded in Pamplona, and ultimately dying on the streets. Unless it’s bull running season the streets of Pamplona are fairly safe, and the worst that was likely to happen if I did get lost and missed the bus was that I’d have to spend the night in that city and start the camino a day later. Despite my catastrophising I caught the bus on time that day, and over the next month I completed the first chapter of what would be my ongoing adventures on the camino.

I’d come a long way since that day in Pamplona in 2004. I’d never encountered a problem on the camino that couldn’t be overcome, and there was never a bad situation that couldn’t have been worse. Apart from some bone drenching downpours, the sky never fell in. And living on the edge always brings a few thrills of its own. Now I knew I was off course, and I had partly allowed that to happen. By not turning around and retracing my steps it would be more difficult to find the way back, but I felt if I kept walking forward, and used a common sense approach to direction and reading the landscape, I’d eventually get to Ourense. It might add a few hours on to my journey, but it would be an adventure. I followed the path out of the forest and onto a country road. It passed through some sleepy villages before leading to a busier thoroughfare. If I headed north I expected I’d be going in the right direction, and within time I found street signs pointing to Ourense. I was on my way again. I walked along the shoulder of a main road for a while, past a series of shuttered hotels and businesses, and finally I spotted a camino shell. I was back on track, just as I expected I would be.

The trail meandered through small villages, along country lanes, and on top of the leaf carpeted floors of deciduous woods for the next few kilometres. The camino merged with other marked cycle paths, but after a certain point, in the middle of a thick forest, the yellow camino arrows disappeared again and once more I found myself lost. This time I wasn’t quite sure what had happened, as I’d been faithfully following the arrows since I’d last picked them up. I found a bus shelter where I had a snack and took refuge from a shower, and tried to decide what to do next. The only option available to me was to determine the right direction, then pick a path, any path, and follow it until I discovered the right one again. Despite having no compass, and the sun being intermittently obscured by cloud cover, I could still make out my bearings. North by northwest was the way to go, and so I ventured again into the woods. As long as I did the walking, I trusted that the Universe would show me the way.

Had I followed the official path I would have arrived in Ourense at noon. As it was I got there at 2 PM. I was a little tired, I’d endured a few unpleasant showers, but I was safe and well and all the better for my detour. I possibly added an extra 10 KM on to my journey, but I had the chance to visit places I wouldn’t otherwise have seen, and I learned, yet again, that the worst rarely comes to pass. It was a micro adventure, the type of activity that gets the blood racing and raises a few fears, but ultimately drags you into the present moment, which is where life is ultimately lived. Getting lost forces you to focus on the now. When you’re in the moment you concentrate on what needs to be done there and then, especially when survival is at stake. We should all allow ourselves to get lost once in a while. The lessons learned in finding the way back might be a lot more valuable than whatever the original purpose of your journey may have been.

The city of Ourense, which dates from Roman times, has a beautiful old town, and a splendid new albergue right in its centre. There was yet another opulent medieval cathedral nearby, but having already seen cathedrals in Malaga, Cadiz, Seville, Caceres, Salamanca and Zamora on this trip I decided to give this one a miss. My brain did not have enough space to process any more gothic and renaissance sculptures. Instead I went to one of the city’s famous thermal baths to soak my bones in an outdoor pool, and let the famous thermal waters work their magic. I was mostly bones by that stage, with whatever flesh I had at the start of the journey being shed on the roads of Extremadura and Castilla y Leon. I wasn’t likely to replenish those lost kilos in Ourense on a national holiday either, as finding an open shop or a restaurant that was serving food before bedtime proved to be a bigger challenge than getting lost in the woods.

The albergue in Ourense was filled with pilgrims old and new. Among the familiar faces were Max, the American with his famous wooden backpack, and his cousin Sahara. I’d known Max since Andalucia. Our paths had overlapped many times. We often lost each other for a week or two, only to bump into each other again several hundred kilometres later. He was planning on spending an extra night in Ourense, and his ultimate goal was to make it down to the Canary Islands and hitch a ride back to the states on a yacht. He left the albergue just slightly before I did the following morning, and I didn’t get the chance to say a proper goodbye. I never found out how his journey finished, and whether he managed to sail back home across the Atlantic. People breeze in and out of our lives on the camino. They arrive without any warning, and they often depart without any ceremony. There frequently isn’t any real closure on a path like this, but the journey continues all the same.

Another Himalayan mountain awaited me as I exited Ourense, but beyond that arduous climb I enjoyed a tranquil day of forested paths and sleepy villages. The next few days rolled by. I spent nights in lacklustre towns called Castro de Dozon and Silleda, where the only familiar faces I saw were Antonio from Spain and Gustavo from Argentina. We’d been on the same route for over a week, and had grown friendly in spite of the lack of a common language. I was growing increasing tired at this point, and I even felt traces of fever as I suited up in the mornings. My body switched to autopilot, and I continued to put one foot in front of the other, knowing that the spirit would eventually catch up with the body. In all my time on the different caminos I had never once wanted to quit, but there were occasions when I looked forward to the journey being over. This was one of those times. Wishing for things doesn’t make them happen, so I had to soldier on in the knowledge that every thing in life is transient: tiredness will give way to enthusiasm, rain will give way to sunshine, and darkness will give way to light. Whatever your mood or the atmospherics, you have to walk on.

The penultimate day led from Silleda to Outerio, a stand alone albergue in the woods about 16 KM from Santiago. The small crowd of diverse pilgrims staying in those lodgings sensed we were now within touching distance of our destination, and we all breathed the air of quiet satisfaction that can only be experienced after completing a monumental undertaking. Herman, who I hadn’t seen since Ourense three nights earlier, made it to Outerio that evening. The king of the caminos was about to claim his 18th compostela. And he had only started walking these paths when he was in his 60s. Antonio said he was about to complete his fourth Via de la Plata, while another Polish man was finishing his sixth pilgrimage. It was only the diehards who chose this particular route, and we all looked at each other with admiration, knowing that we had successfully overcome all the obstacles and hardships, and we’d managed to stay the course. Whatever knocks we took along the way we took in our stride, and we wouldn’t have had it any other way.

We had all stocked up in a local supermarket earlier in the day. Being bound together by the camaraderie of the camino we shared what provisions we had with each out of a sense of duty and goodwill. The hospitalero, by contrast, had more in common with a POW camp guard. He made regular inspections of the facilities, and removed any items of clothing that were placed on top of the heaters. We worked out a system to time his rounds, and we cleared the radiators just before he appeared, and then put everything back just after he left. Hospitaleros could be a strange bunch. Some were the most friendly and accommodating people, who couldn’t do enough to help you, and then there were those who saw you as a security threat and would monitor your behaviour like a prison warden. Leaving their establishments after a night could feel like escaping from Alcatraz. Raucous fights occasionally broke out between the more inflexible hospitaleros and the more demanding pilgrims. I always found it funny when arguments occurred, because it showed the disconnect between what people expect from the camino and the reality. Those who see it as a holiday and expect five star treatment in an albergue are going to be disillusioned. If that’s what you want go to Marbella. One immutable rule of the camino is that a pilgrim never demands, but gives thanks for what they receive. If you follow that philosophy, you’ll never be disappointed. But you’ll occasionally need to dry your clothes on the radiators as well, so it sometimes doesn’t hurt to hoodwink the hospitalero either.

And so arrived the day when it was time to march into Santiago. It was Tuesday, the 5th of November. Trumpet blasts of angel song didn’t radiate from the heavens to mark the occasion. By contrast the skies above looked mischievous, and indeed they teased us with a few unpleasant showers from time to time, but the sun came out for a few cameos as well. It was a short walk of 16 KM to the city, so even at a gentle pace I could still expect to arrive before noon. The approach into cities can often be ugly and industrial, but the last few KM of the Via de la Plata were pleasant pastoral scenes of corn and forests, with a few trellis lined avenues of vines. I didn’t think grapes grew this far north, but the few I sampled tasted just fine. The bollards measuring the distance showed ever decreasing numbers. It was now down into single figures, and after 36 days on the road the great city seemed tantalisingly close.

As I walked down a hill one of my extendable walking poles retracted unexpectedly. I stopped to take it apart and adjust some of the locking mechanisms but no matter what way I calibrated them the pole still retracted as soon as I put any weight on it. I trundled on for a while with one working stick and one unextended one. I even tried walking lopsided to see if I could use the pair of them together. I couldn’t. I’d need to find something to insert into it to keep it steady. This wasn’t a problem I wanted to face, but it could be overcome. However, a short time later a slightly more threatening scenario arose. Very suddenly I felt a very strong tightening in my chest. I found it difficult to breathe and stand up straight, and for a moment I thought I might be having a heart attack. It would be most unfortunate if, having endured all the challenges of the Via de la Plata, it was my own ticker that gave out just as I was in the shadow of the cathedral. I paused, took a few deep breaths, tried my best to stand up straight, and – like any other man in his 40s who is faced with a potentially life threatening illness – I ignored it in the hope that it would go away. Not even a heart attack was going to prevent me from getting to Santiago. As expected, the pain did go away. It was not a good day to die. Later on up the road I found a twig which I was able to wedge into my walking stick to prevent it from collapsing. With all major problems solved it was full speed ahead to the journey’s end.

Entering Santiago can often provide a rush of emotions. The first time I arrived, I wandered through the streets of the old quarters, full of enthusiasm for this magical medieval metropolis that I had spent more than a month walking to. The last time I was here, having completed the Norte/Primitivo, I succumbed to a few tears of joy when I reached the city limits. This time round the heavens opened again, so I let the clouds do all the crying as I made my way towards the centre. The Via de la Plata enters the city from the south, through neighbourhoods I hadn’t previously visited. I caught sight of the Baroque spires of the cathedral in the distance, which was the first familiar place I had seen since I started this journey. It felt like I was home.

The rain increased in intensity as I neared the centre. This was just the kind of good old fashioned Galician welcome I expected. The yellow arrows had now disappeared, but I didn’t need them any more. I knew the way by this point. Crossing the road at the busy Praza de Galicia, I entered the crowded narrow streets of the old city. The locals hurried about, paying little attention to yet another wizened pilgrim who had managed to walk a long way to their home town. I was just focused on getting to the cathedral to complete my journey, and of course take the obligatory money shot in the shadow of its spires. And didn’t the heavens oblige by letting the sun come out just as I got there.

Praza de Obradoiro is the Emerald City at the end of the Yellow Brick Road. A magnificent square, overlooked by the awe inspiring cathedral, it is there that all pilgrims head when they first get to Santiago. Throughout the year it is normally thronged with people celebrating the completion of their journey, but it was now November and the city was closing up for the season. Echos of plaintive bagpipe music wafted in from the surrounding side streets, but the excited chatter of pilgrims was conspicuously absent. I looked up at the tall, imposing spires, and the statue of Saint James that stands between them. The facade had been receiving a thorough facelift on my previous trips to the city, but that process was now complete and the cathedral’s glorious baroque features were again on show for everyone to enjoy. It was so nice to be back.

The contrast with the cathedral’s interior, however, could not have been more pronounced. For years, the inside of this great building was starting to look its age. A few coats of paint were more than needed to spruce the place up a bit. Such a move had obviously been on the to do list of this church’s overseers, but I got quite a shock to see that virtually the entire inner building was wrapped in plastic. All the pews were removed, there was no sign of the famous incense burner, the Botafumiero, and only the alter and crypt were still accessible to the public. Whatever one’s spiritual motives for walking the camino, there is a great sense of closure when attending the high mass at the cathedral, and witnessing the incense burner being set alight and thrust up into the rafters, while the organ blares transcendent music into all corners of the building and into the souls of the congregation. That spectacle was now gone. Rumours were that it would take ten years before the cathedral’s interior was fully restored. I climbed up behind the alter to perform the ritualistic embrace of Saint James’s statue and give thanks for my safe arrival. His stately position offered him the best view in the house, but I sensed that he now looked down the nave of his great church with a tear in his eye. It would come good again, but it would take time.

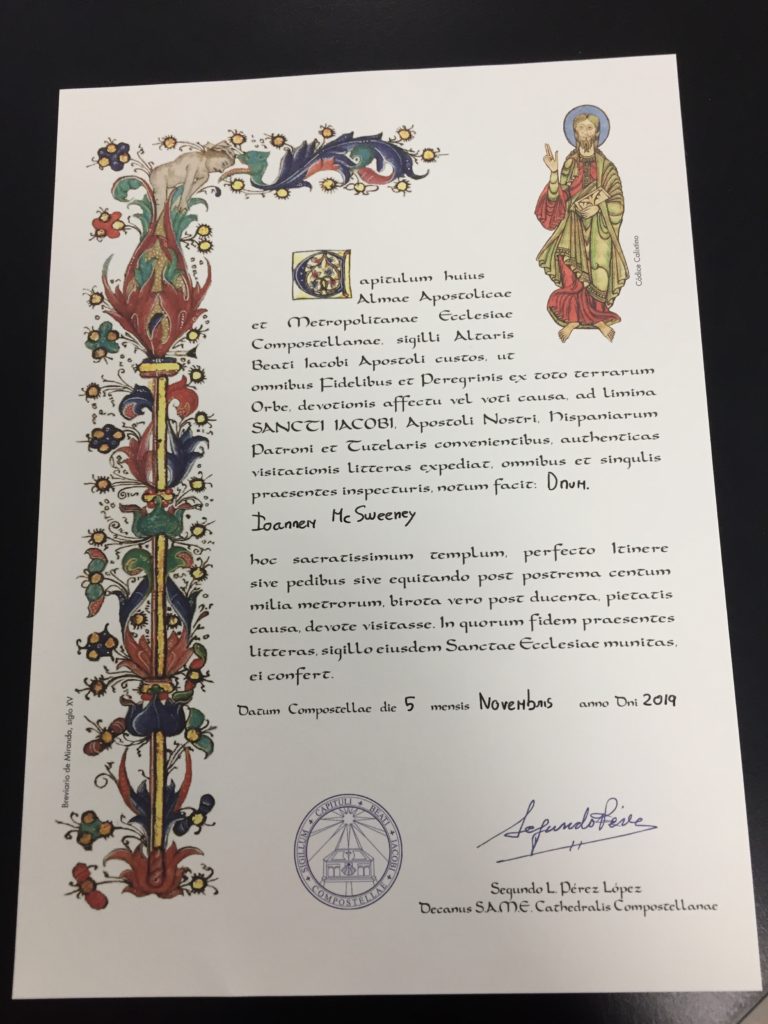

Later at the Pilgrims’ Office the guy who was issuing me the compostela told me that I should have got two stamps per day during the last 100 KM. That might be fine on the Francés, I wanted to tell him, where there was a cafe, bar or albergue every 50 metres, but on the Via de la Plata I was lucky if I could find one place each day to get food, let alone two to get stamps. And did he really think that I might have cheated and taken the bus for portions of the last 100 KM, having walked through deserts, windswept plains, crossed mountains, foraged for food (metaphorically speaking), fended off angry dogs and wild bees, and stood down a group of hunters? I’d earned my compostela, and if he wanted to argue with me I was quite happy to fight him. But he just said to make sure I got two stamps per day next time. Afterwards, I wondered how did he know there would be a next time? Perhaps he recognised a camino veteran when he saw one. Whatever he read in my face, it must have said that one camino would never be enough. He was right, I suspect. I would be back.

Daniel from Israel was in town the day I got to Santiago. I hadn’t seen him since Burger King in Salamanca, about 500 KM before. We wandered out of the city centre to a massive modern shopping mall on the outskirts, where we had a catch up in an environment that felt a million miles away from the camino, in spite of being located only about 200 metres from the last stretches of the Francés. It was good to see a familiar face. One of the reasons why Santiago feels like home is because I have always encountered familiar faces on its streets. Those people may have been unknown to me a few weeks earlier, but the duration of a friendship is irrelevant if you’ve shared a part of the camino together. The bond between fellow pilgrims is as strong as those forged among soldiers in wartime. Some of us may remain friends for life, while others may slowly fade from our radars, but none of us ever forget the people we’ve met along the roads to Santiago. Those friendships are what the camino is ultimately all about.

Daniel and I wandered back into the centre and said farewell outside the cathedral. He had an early morning flight back home, while I still had more business in Galicia. For me, the camino never finished in Santiago. To get all philosophical about it the camino never ends, but I always had to walk to the end of the world in Finisterre, and if time allowed back to Santiago, before I felt I had earned the right to go home. I had trekked the path to Finisterre and Muxia many times. I was familiar with most of its twists and turns, its bumps and hollows, and its charms and terrors. It was a camino with which I had a tempestuous relationship. I had endured some of my most difficult days along those roads, as well as some of my most enjoyable. Having already walked 1,000 KM, a further 200 KM was both an added challenge and a reward. I knew what to expect of the path to come, and I looked forward to revisiting old haunts, but the journey would be new. It was time for the final odyssey.